by Zarifah Anuar

I fight a lot with my parents. I think that’s inevitable when you’re an opinionated young adult whose views are a direct contrast to those of your conservative parents, but the most recent argument topic was quite strange to me. It was about time and planning.

I’m a planner. I have a bullet journal where I schedule everything — work, meetups with friends, family obligations, even my own me time. I like organising my week and knowing what’s in store for me in the days to come.

My parents are different. They’re not quite spontaneous, not quite planners. They know what they have in the future and sort of just file it away until the day approaches.

Which leads to clashes that look a little bit like this:

“Kakak, are you free tomorrow?” my dad would say on a Friday night.

“No, why?” I would ask, though I know well what it is.

“Can you ikut [follow] your aunt pergi Johor ambik Atuk?” He would say. He would not sound sheepish, because this would not be the first time. Or the third. Or the fifth. I have lost count the number of times he has asked me if I’m free the next morning to do a four hour drive up to Segamat to fetch my grandfather.

“I can’t, I’m not free,” I would repeat. I would be trying to stay calm, but I really can’t. “Why didn’t you tell me earlier? She always schedules these way ahead what.”

“Yeah, I’m just asking,” my dad would retort.

“You know if you were to ask me, like, on Monday, I would set aside Saturday for this,” I would reply.

“It’s okay, you’re always so busy. Got friends to meet with,” he or my mother would say, and I wouldn’t miss the sarcasm in their voice.

“Not always. You know I will always set aside time for family.”

“No, you will always set aside time for your friends,” either one of them would reply — the ultimate killer line, and it would hurt.

It hurts because I try my best to put family above everything else, but it gets really hard to do so when I’ve already made plans ahead with friends, and it would be ridiculous to cancel them every time my parents want me to do something for the family — which is, well, every other week.

Perhaps it’s some kind of generation gap — when my parents were twenty-five they were already married, and life revolved around their families and work, in that order. At twenty-five my life revolves around my work, family, friends, and my hobbies, though the order gets kind of jumbled sometimes.

There is this expectation that family should hold the same level of importance for me as it did for them. In many ways this is still true, because I was a caretaker for my grandparents when they were in the hospital. I still do take leave to care for them when necessary. When asked, I also try to be involved in whatever big event that’s getting my extended family excited — be it a wedding or a birthday.

Is that not enough? Perhaps the older generation expects initiative where I can only give participation. And to me, my participation is an expression of my filial piety and love for my family, but to them it equates to family being less important. Less of a priority.

In today’s society where women are expected to play a myriad of roles and hold an assortment of responsibilities, I find myself lost in what is important, and to whom it is important. To me, family is important, and so is a career and nurturing meaningful friendships. To my parents and grandparents, it would be more meaningful if I were to put the energy I spend on my friends into finding a suitable candidate for marriage.

Unsurprisingly, the burden of caregiving seems to fall more on women even as more opportunities are opened up to them. We don’t hold our sons up to the same standards we hold our daughters up to, even as we allow our daughters to pursue careers and interests beyond the home and family.

As a daughter, the definition of filial piety is caregiving: to my grandparents, my parents, and my brother, coupled with the looming shadow of marriage constantly hovering over me. When I say that I’m not looking for marriage and I don’t intend to bear children, I’m constantly told that I will change my mind, that it is in my nature, as a woman, to desire companionship and offspring.

Even the concept of marriage and childbearing in our community is seen as something that is not personal, but a journey that the family takes together. You don’t just marry your partner; you marry into their entire family as well. Similarly, you’re not just carrying your child, but also your parents’ and in-laws’ grandchild.

With this mindset it’s easy to assume that every woman’s life should follow a certain template, especially with the exciting expectations that come along with certain milestones such as marriage and pregnancy. Even with the myriad of opportunities available to women now, filial piety in the form of caregiving, marriage, and bearing the next generation still seem to be expectations that are highly valued by the family and community.

Some time back I shared with my grandmother that one of my second cousins was getting married. She was overjoyed, saying, “Alhamdulillah, untung mak bapak dia, sekarang dorang boleh relax, dia boleh jaga.”

It left me confused. Won’t getting married mean that she would have even less time to care for her own parents, because now she would also have to care for her in-laws and husband as well? And once she has children, won’t that increase her caregiving burden even more? Why is marriage seen as something necessary for a woman to go through in order to ‘level up’ and be an even better caregiver?

One of my role models growing up, and to this day, is my aunt. She isn’t married, but has an amazing career and is the main caretaker of my grandparents — all of which I aspire to be when I am older. She recently shared that the reason why she didn’t feel particularly burdened by expectations of marriage was that her mother never imposed such expectations onto her.

Perhaps, that is what we as women need from each other — freedom of burdensome expectations, and validation of our own desires and aspirations. When I look at my aunt all I see is an ideal portrait of my future, when in another’s eyes it would be pity. But why? She is an independent, successful, filial, religious woman. So why would lacking a husband and a child make her seem less to others?

_

Zarifah Anuar is a writer, graphic designer, educator, and a volunteer with AWARE and Gender Equality is our Culture. She also co-runs Penawar, a support group for women with religious trauma.

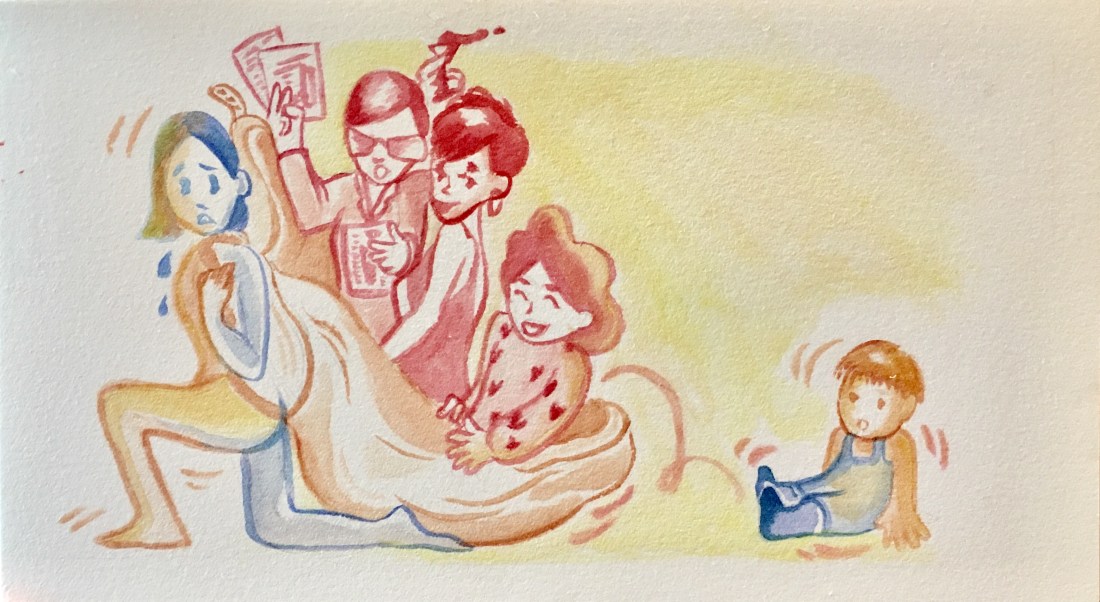

Illustration by Ishibashi Chiharu

Nice read and thanks for sharing. I also felt this when i was younger and had to drive my mum around places or make time for them spontaneously. Though after I moved out of home that all kind of stopped. I’ve since moved to Singapore to live and after a year here, I do see myself going home soon, and one of the things I want to do is ferry my mum around more as she gets older. Its funny how it goes full circle sometimes

LikeLike